A Narrative History of Environmentalism's Partisanship

This is the second in a sequence of four posts taken from my recent report: Why Did Environmentalism Become Partisan?

Many of the specific claims made here are investigated in the full report. If you want to know more about how fossil fuel companies’ campaign contributions, the partisan lean of academia, or newspapers’ reporting on climate change have changed since 1980, the information is there.

Introduction

Environmentalism in the United States today is unusually partisan, compared to other issues, countries, or even the United States in the 1980s. This contingency suggests that the explanation centers on the choices of individual decision makers, not on broad structural or ideological factors that would be consistent across many countries and times.

This post describes the history of how particular partisan alliances were made involving the environmental movement between 1980 and 2008. Since individual decisions are central to understanding why this happened, this history is best presented as a narrative following the key people and organizations.

Environmentalism in the Reagan Era

In the wake of the New Deal, the Republican Party acquiesced to the government having a larger role in society than it had had before the Great Depression.1 Republican presidents would sometimes support increased government spending and regulation. This is apparent in environmental policy: Nixon was involved in several major pieces of environmental legislation and created the EPA in the executive branch.

The election of Reagan in 1980 reoriented the Republican Party. It would now advocate for a smaller government: less (non-military) spending, lower taxes, and less regulation. The free market would provide many of the services that had previously been done by the government. Thatcher’s election as Prime Minister had similar results for the Conservative Party in the UK.

This might seem like it would cause a deep ideological conflict: Environmentalists advocated for regulations on private enterprise and international cooperation on policy, while the Republican Party preferred private and local action. However, this is not what we observe with either Reagan or Thatcher.

The conservative leaders in the US and UK supported environmentalism, even when it involved international regulations. The clearest example of this is the Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer in 1988. Reagan described it as:

The Montreal protocol is a model of cooperation. It is a product of the recognition and international consensus that ozone depletion is a global problem, both in terms of its causes and its effects. The protocol is the result of an extraordinary process of scientific study, negotiations among representatives of the business and environmental communities, and international diplomacy. It is a monumental achievement.2

The US Senate ratified the Montreal Protocol unanimously.3

Reagan and Thatcher also specifically supported international regulation to combat climate change. Thatcher was the first head of government to talk about climate change at the UN, in 1989, and called for an international conference on climate change in 1992 (The Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro).4 The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) creates the reports summarizing the scientific consensus about climate change, and its “principal architect was the conservative Reagan administration.”5 In 1992, the U.N. Framework Convention of Climate Change (UNFCCC), the result of the Rio Summit, had the support of the Bush Sr. administration. The U.S. Senate decided that it was popular enough to not need a roll-call vote.6

These actions of conservative leaders also translated into broad popular support, including among Republicans. The 1980s saw increasing concern about the environment and a decreasing partisan gap. Republicans only became anti-environmentalist after 1990.

Anti-environmentalism is not the natural consequence of the small government ideology of Reagan and Thatcher. It only entered the US Republican Party a decade later, and the UK Conservative Party has continued to support environmentalism.

Environmentalists, Climate Scientists, & Democratic Politicians

The earliest partisan alliances involving climate change began in Congressional hearings in the 1980s.

The Reagan administration entered office promising to reverse most of the energy policies of the Carter administration and dramatically shrink the Department of Energy, which had just been created in 1977.7 One of the programs cut was a newly established center for climate research.8 As an undergraduate student, Al Gore had taken classes in climate science from Roger Revelle, one of the first people to study global warming. In the House of Representatives, Gore led Congressional hearings against these particular cuts (which were partially reversed), and continued to be very involved whenever climate was an issue in Washington.9 Climate policy at this time was still bipartisan, and the Reagan administration was open to government action on climate.

The environmental movement also became increasingly interested in climate change in the late 1980s, particularly after the summer of 1988. This summer saw severe drought across most of the U.S., low enough water in the Mississippi River to hinder barge traffic, heat waves, major fires in Yellowstone, and a Category 5 hurricane in the fall. In and after a Congressional hearing on the climate, James Hansen of NASA claimed that he was “99 percent certain” that “the greenhouse effect is here.”10 Many other climate scientists did not believe that the evidence was that strong yet and disliked his combative tone. A few publicly rebuked him.11

Focusing on climate change provided a way to unify the disparate concerns of the environmental movement, including air & water pollution, habitat conservation, recycling, and energy production. The historian of science Spencer Weart describes this transition as:

The environmental movement, which had found only occasional interest in global warming, now took it up as a main cause. Groups that had other reasons for preserving tropical forests, promoting energy conservation, slowing population growth, or reducing air pollution could make common cause as they offered their various ways to reduce emissions of CO2.1213

An unusually explicit statement of this strategy comes from Senator Timothy Wirth (D-CO):

What we've got to do in energy conservation is try to ride the global warming issue. Even if the theory of global warming is wrong, to have approached global warming as if it is real means energy conservation, so we will be doing the right thing anyway in terms of economic policy and environmental policy.14

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, environmentalists became increasingly focused on climate science, and both environmentalists and climate scientists formed political alliances with Democratic politicians.

The Clinton-Gore Administration and the BTU Tax

In 1992, Bill Clinton selected Al Gore as his vice presidential candidate and secured the endorsements of environmental organizations like the Sierra Club that had mostly stayed above the partisan fray.

One of the Clinton’s administration’s early legislative goals was a tax on energy, measured in British thermal units (BTUs).15 While this is sometimes remembered as an attempt at a carbon tax, it taxed energy rather than carbon dioxide. Solar, wind, and geothermal power production were exempted, but nuclear and hydroelectricity were not. This tax proved extremely unpopular. To shore up support, the Clinton administration agreed to more exemptions for particular industries, but this diminished what the bill hoped to accomplish, did not improve its popularity in Congress, and encouraged even more groups to request exemptions.16 The broad-based BTU tax was abandoned, and replaced with a much weaker tax on gasoline. Congressmen who had supported the BTU tax suffered politically in the midterms.

In 1994, Republicans won control of the House of Representatives for the first time in 40 years. The BTU tax was not the only significant issue: the NRA also organized against an assault rifle ban and Newt Gingrich innovated by using a national strategy instead of focusing on individual races. Opposing a climate policy was one thing that helped propel Republicans into power in Congress.

Fossil Fuel Companies, Climate Skeptics, & Conservative Think Tanks

The fossil fuel industry opposed government action on climate change. Significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions would completely undermine their business model, forcing them to transition to a different industry (renewable energy) or dramatically lose market share. In 1989, a group of fossil fuel and manufacturing companies founded the Global Climate Coalition to oppose climate policy that they claimed would disrupt the American economy.17 The Global Climate Coalition spent tens of millions of dollars in ad campaigns and contributions to politicians before it disbanded in 2001.

At the time, it was not obvious that the industry lobbying would overwhelmingly favor Republicans. There had not previously been a strong tendency for fossil fuel companies to support Republicans.

It is not too surprising that the industry lobby ended up favoring Republicans. Republicans were the more business-friendly party. There was already a small bias for campaign contributions in that direction and oil is more concentrated in Republican-leaning states. The Gulf War in 1990 might have associated the oil industry with the Republican Party, although the war proved broadly popular.18 Academics, probably including climate scientists, were somewhat more likely to lean to the left, although not nearly as much as they do today. Congressional Republicans had been somewhat more likely to oppose environmental legislation than Congressional Democrats for several decades. But then there was an abrupt change in the early 1990s, and this difference dramatically increased.

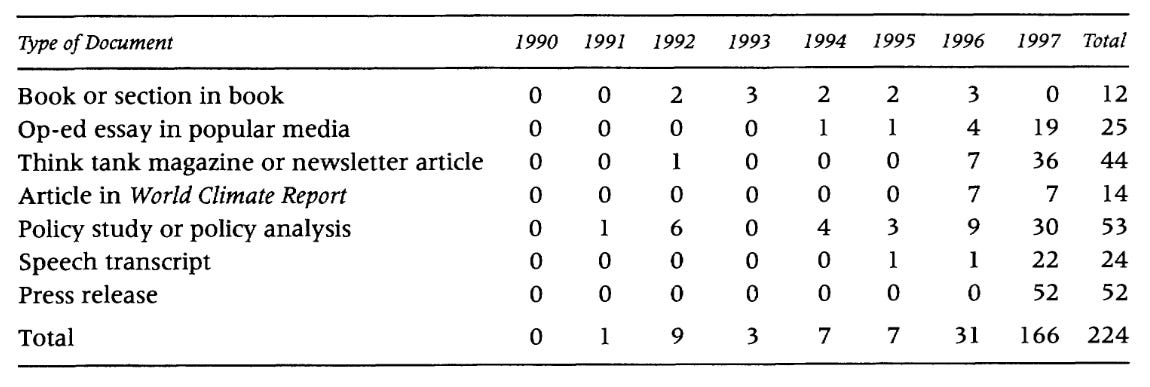

The Global Climate Coalition found willing allies among conservative think tanks. These think tanks would accept funding from the fossil fuel industry to hire skeptical climate scientists or experts from other fields who were skeptical of climate change. They would publish policy studies, newsletter articles, and press releases that cast doubt on conventional climate science and opposed climate policy proposals. These think tanks and skeptics were successful at reframing the climate debate and creating the “non-problematicity” of global warming among conservatives. The most common claims by conservative think tanks were that “the scientific evidence for global warming is highly uncertain” and “proposed action would harm the national economy.”19

It is not clear to me whether the causal relationship mostly points from conservative think tanks to Republican congressmen or vice versa. The first climate skeptic publication by a major conservative think tank was in 1991, before Clinton & Gore were elected or Gingrich became Speaker of the House. However, there were initially only single digits of publications per year, mostly by a single think tank: the Marshall Institute. The publications did not become common or widespread until 1996-1997. Between 1991 and 1996, most conservative think tanks did not yet have a public position on climate change.

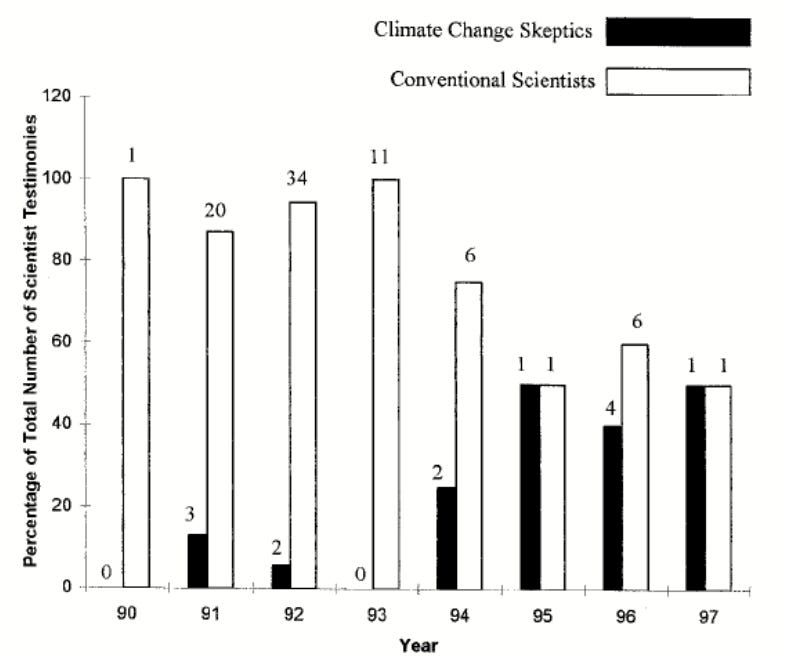

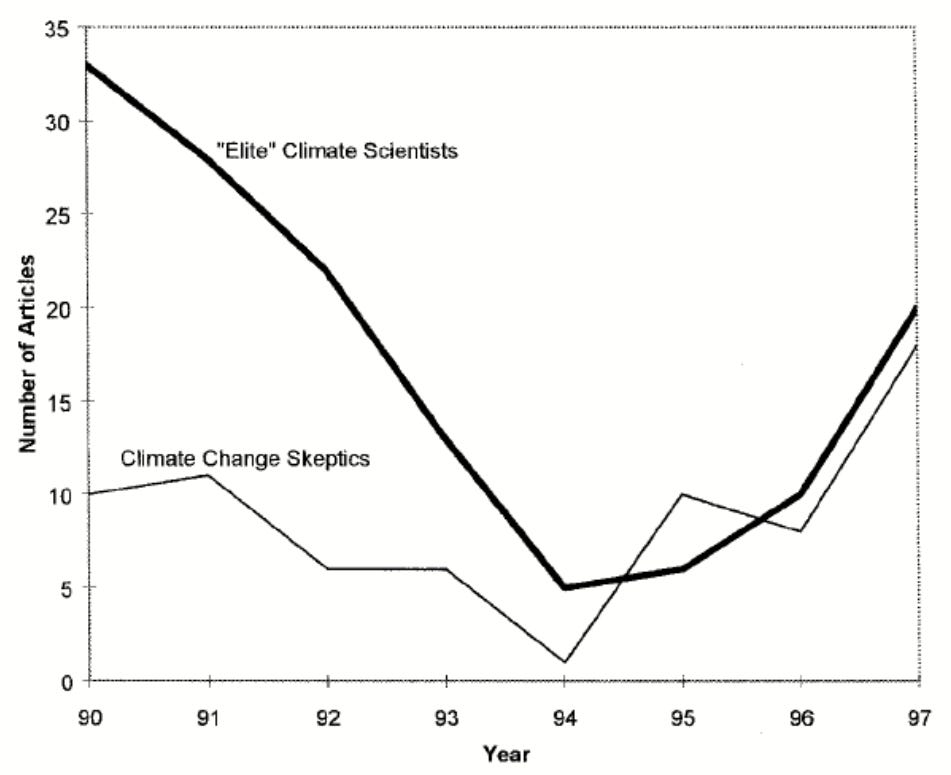

After the Republican Party led by Gingrich won the Midterm elections in 1994, the number of Congressional hearings about climate change decreased. When there were hearings, Congress would invite similar numbers of conventional climate scientists and climate change skeptics.20 Congress began to treat this as an active scientific debate and the media followed suit,21 even though both had previously predominantly presented the scientific consensus.

Debates Over the Kyoto Protocol

The Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 which had produced the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) also called for a future summit, in Kyoto, that would impose limits on countries’ greenhouse gas emissions.

While the UNFCCC had gotten broad bipartisan support under the Bush Sr. administration, the politics of climate change had changed dramatically since then. The debate over the Kyoto Protocol would see the last major bipartisan actions on climate change and the beginning of substantial partisanship among the public.

Before the summit, the US Senate unanimously passed the Byrd-Hagel Resolution, which declared that it would not support any treaty that imposed restrictions on developed countries (like the US) but not developing countries.22

The summit was very contentious and the negotiations almost collapsed. On the last day, Vice President Gore flew to Kyoto to save the agreement. The resulting Kyoto Protocol did not impose any restrictions on the greenhouse gas emissions of developing countries. President Clinton signed the treaty, but did not even submit it to the Senate for consideration.23 To win, it would need 2/3 of the Senate, who had just unanimously opposed it.

I am uncertain whether this should be thought of more as a case where the Senate overconstrained the international negotiating position of the presidential administration or more as a case of the administration ignoring the advice of the Senate.

Before and during the summit, the Clinton administration ran a media campaign to build public support for the resulting treaty. There was a massive increase in media coverage, most of which was aligned with conventional climate science. Conservative think tanks also dramatically increased their production of skeptical media. A pair of surveys conducted before and after this debate found that it did make people more aware of climate change as an issue. A majority of people believed that climate change was going to happen, was going to be bad, and that the government should limit air pollution to address it. The overall percentages of people who supported these positions did not change as a result of the debate. There were underlying shifts as strong Democrats came to increasingly support the administration’s policy and strong Republicans came to oppose it.24

The Kyoto Protocol was a failed attempt at climate policy in the United States that directly increased partisanship.

Continued Increases in Partisanship

Partisanship continued to increase after the debate over the Kyoto Protocol.

Al Gore ran for president in 2000. Although he was strongly associated with climate change by this point, multiple sources claimed that environmentalism was not a major issue in this election.25 Bush Jr. became president instead, declared that the U.S. would not fulfill its obligations under the Kyoto Protocol, and reduced funding to climate science.26

During this time, some of the structural factors that might have been contributing to rising partisanship ended. The Global Climate Coalition disbanded in 2001. Some of the companies which had been involved accepted climate change, while others continued to promote skepticism. The mainstream media stopped presenting both sides of the debate in 2003-2004. Nevertheless, the partisan gap continued to grow.

In 2006, Gore released a climate change documentary titled An Inconvenient Truth. This did not change overall public opinion.27 Instead, partisanship continued to increase: more Democrats were becoming climate activists, while Republicans were becoming increasingly skeptical.

There were still prominent Republicans who supported policies to counteract climate change. Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger introduced a cap-and-trade system for California,28 while Senator John McCain co-sponsored a bill that would create a similar system for the country.29 However, an increasing number of Republicans became increasingly opposed to environmentalism, and the environmental movement became increasingly tied to the Democratic Party.

Subsequent decisions by both parties, and the environmental movement itself, continued to contribute to rising partisanship on environmental issues in the United States.

Conclusion

Broad structural and ideological differences do not explain the partisanship of environmentalism. During the Reagan and Bush Sr. administrations, the Republican Party did support environmentalism, including international agreements on climate change, despite its small-government orientation on most issues. The Republican Party did not significantly change its ideology between the 1980s and 2000s. The subsequent partisanship in environmentalism then cannot be explained by foundational ideological differences between Democrats and Republicans. Instead, the explanation involves a history of alliances made by particular decision makers.

The first alliance made was between environmentalists, climate scientists, and Congressional Democrats during Congressional hearings in the 1980s. The key figure here was Al Gore. Environmentalists seemed to accept the usefulness of this alliance and did not seriously try to find a similarly prominent or rising Republican politician to ally with as well.

The second alliance made was between fossil fuel companies, climate skeptics, and conservative think tanks, starting around 1990. The industry organized into the Global Climate Coalition in 1989 and convinced the Marshall Institute to begin publishing climate skepticism in 1991. For a few more years, this alliance was not complete: most conservative think tanks were still neutral on climate change, and environmentalists might have been able to convince some of them to support their cause.

When environmentalist-aligned Democrats were in political power in the 1990s, they made several policy proposals that were deeply flawed. A tax proposed in 1993 taxed energy produced, not carbon dioxide emitted, and included arbitrary exemptions. The Kyoto Protocol in 1997 contained terms that the Senate had previously rejected unanimously. These flawed policy proposals made it easier for Republicans like Gingrich or Bush Jr. to rally the public against them – and environmentalism more broadly. Subsequent decisions, on both sides of the aisle, continued to reinforce the trend towards increasing partisanship.

This partisanship could have been avoided, if various decision makers had made different choices about what alliances to form or not form. Environmentalism is not partisan in many other countries, including in highly partisan countries like South Korea or France. The resulting partisanship was bad for the environmental movement. As partisanship increased in the 1990s and early 2000s, environmentalism saw flat or falling support, fewer major legislative accomplishments, and fluctuating executive actions.

Prior to the Great Depression, there was less disagreement between the two parties about what the size of the government should be. The New Deal saw Democrats dramatically increase the size and role of the governments, which Republicans initially opposed.

Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. U.S. Department of State. (Accessed April 17, 2024) https://www.state.gov/key-topics-office-of-environmental-quality-and-transboundary-issues/the-montreal-protocol-on-substances-that-deplete-the-ozone-layer/.

Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. Senate Consideration of Treaty Document 100-10. (1988) https://www.congress.gov/treaty-document/100th-congress/10.

Margaret Thatcher. Speech to United Nations General Assembly (Global Environment). (1989) https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/107817.

Spencer Weart. The Discovery of Global Warming. Government: The View from Washington. (Accessed Feb 2024) https://history.aip.org/climate/Govt.htm.

The UNFCCC was ratified using a division vote, in which Senators stand for “yea” and “nay” and the presiding officer counts the number of Senators standing for each. The result of the vote is not recorded other than whether it passed. Treaties require 2/3 support of the Senate to be ratified, so it had to have had significant bipartisan support. Typically, division votes and voice votes are used when the result of the vote is not in doubt beforehand.

About Voting. U.S. Senate. (Accessed March 22, 2024) https://www.senate.gov/about/powers-procedures/voting.htm.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Senate Consideration of Treaty Document 102-38. (1992) https://www.congress.gov/treaty-document/102nd-congress/38.

Republican Party Platform of 1980. § Energy. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/republican-party-platform-1980.

Climate Change in the 1970s. American Institute of Physics. (Accessed March 29, 2024) https://history.aip.org/history/exhibits/climate-change-in-the-70s/.

Spencer Weart. The Discovery of Global Warming. Government: The View from Washington. (Accessed Feb 2024) https://history.aip.org/climate/Govt.htm.

Roger A. Pielke Jr. Policy history of the US Global Change Research Program: Part I. Administrative development. Global Environmental Change 10. (2000) p. 9-25. https://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/admin/publication_files/2000.09.pdf.

Philip Shabecoff. Global Warming Has Begun, Expert Tells Senate. New York Times. (1988) https://www.nytimes.com/1988/06/24/us/global-warming-has-begun-expert-tells-senate.html.

Richard A. Kerr. Hansen vs. the World on the Greenhouse Threat. Science 244. (1989) https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.244.4908.1041.

Spencer Weart. The Discovery of Global Warming. The Public and Climate Change Since 1980. (Accessed Feb 2024) https://history.aip.org/climate/public2.htm.

Scott Alexander has also noticed this transition and described it as:

It feels almost like some primitive barter system has been converted to a modern economy, with tons of CO2 emission as the universal interchangeable currency that can be used to put a number value on all environmental issues.

Scott Alexander. What Happened To 90s Environmentalism? Slate Star Codex. (2019) https://slatestarcodex.com/2019/01/01/what-happened-to-90s-environmentalism/.

Roger A. Pielke Jr., Roberta Klein, & Daniel Sarewitz. Turning the Big Knob: An Evaluation of the Use of Energy Policy to Modulate Future Climate Impacts. Energy and Environment, 11. (2000) p. 255-276. https://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/about_us/meet_us/roger_pielke/knob/text.html.

Some history. Carbon Tax Center. (Accessed March 29, 2024) https://www.carbontax.org/some-history/.

Dawn Erlandson. The BTU Tax Experience: What Happened and Why It Happened. Pace Environmental Law Review 12.1. (1994) https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1528&context=pelr.

Global Climate Coalition. Source Watch. (Accessed March 29, 2024) https://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/Global_Climate_Coalition.

GCC's position on the climate issue. Global Climate Coalition. (Archive: Feb 9, 1999) http://web.archive.org/web/19990209102342/http://www.globalclimate.org/MISSION.htm.

David W. Moore. Americans Believe U.S. Participation in Gulf War a Decade Ago Worthwhile. Gallup (2001) https://news.gallup.com/poll/1963/americans-believe-us-participation-gulf-war-decade-ago-worthwhile.aspx.

Aaron M. McCright & Riley E. Dunlap. Challenging Global Warming as a Social Problem: An Analysis of the Conservative Movement's Counter-Claims. Social Problems 47.4. (2000) p. 499-522. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237371278_Challenging_Global_Warming_as_a_Social_Problem_An_Analysis_of_the_Conservative_Movement%27s_Counter-Claims.

Peter J. Jacques, Riley E. Dunlap, & Mark Freeman. The organisation of denial: Conservative think tanks and environmental scepticism. Environmental Politics. (2008) p. 349-385. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09644010802055576.

Aaron M. McCright & Riley E. Dunlap. Defeating Kyoto: The Conservative Movement's Impact on U.S. Climate Change Policy. Social Problems 50.3. (2003), p. 348-373. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228594257_Defeating_Kyoto_The_Conservative_Movement%27s_Impact_on_US_Climate_Change_Policy.

The newspapers included are: Wall Street Journal, USA Today, New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, and Newsday.

Aaron M. McCright & Riley E. Dunlap. Defeating Kyoto: The Conservative Movement's Impact on U.S. Climate Change Policy. Social Problems 50.3. (2003) p. 348-373. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228594257_Defeating_Kyoto_The_Conservative_Movement's_Impact_on_US_Climate_Change_Policy.

A resolution expressing the sense of the Senate regarding the conditions for the United States becoming a signatory to any international agreement on greenhouse gas emissions under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Senate Resolution 98. (1997) https://www.congress.gov/bill/105th-congress/senate-resolution/98.

United States Signs the Kyoto Protocol. Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs. (1998) https://1997-2001.state.gov/global/global_issues/climate/fs-us_sign_kyoto_981112.html.

Jon A. Krosnick, Allyson L. Holbrook, & Penny S. Visser. The impact of the fall 1997 debate about global warming on American public opinion. Public Understanding of Science 9. (2000) p. 239-260. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=1ecba8f2535dd16fe855168cfeb35592e36259be.

Steven Kull. Americans on Global Warming: A Study of U.S. Public Attitudes. Program on International Policy Attitudes. (1998) https://publicconsultation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/GlobalWarming_1998.pdf.

Spencer Weart. The Discovery of Global Warming. Government: The View from Washington. (Accessed Feb 2024) https://history.aip.org/climate/Govt.htm.

Gerald M. Pomper. The 2000 Presidential Election: Why Gore Lost. Political Science Quarterly 116.2. (2001) p. 201. https://www.uvm.edu/~dguber/POLS125/articles/pomper.htm.

Thomas E. Mann. Reflections on the 2000 U.S. Presidential Election. Brookings. (2001) https://www.brookings.edu/articles/reflections-on-the-2000-u-s-presidential-election/.

Text of a Letter from the President to Senators Hagel, Helms, Craig, and Roberts. George W. Bush White House Archives. (2001) https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2001/03/20010314.html.

Deborah Lynn Guber. A Cooling Climate for Change? Party Polarization and the Politics of Global Warming. American Behavioral Scientist 57.1. (2013) p. 93–115. https://cssn.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/A-Cooling-Climate-for-Change-Party-Polarization-and-the-Politics-of-Global-Warming-Deborah-Guber.pdf.

California’s Cap-and-Trade Program: Frequently Asked Questions. Legislative Analyst’s Office: The California Legislature’s Nonpartisan Fiscal and Policy Advisor (2023) https://lao.ca.gov/Publications/Report/4811.

Climate Stewardship Act. S.139. (2003) https://www.congress.gov/bill/108th-congress/senate-bill/139/all-info.

Marianne Lavelle. John McCain’s Climate Change Legacy. Inside Climate News. (2018) https://insideclimatenews.org/news/26082018/john-mccain-climate-change-leadership-senate-cap-trade-bipartisan-lieberman-republican-campaign/.