Paper Summary: Princes and Merchants: European City Growth Before the Industrial Revolution

by J. Bradford de Long and Andrei Shleifer. (1993)

https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/shleifer/files/princes_merchants.pdf.

Summary: Freer societies have faster economic growth.

One of the oldest themes in economics is the incompatibility of despotism and development. Economies in which security of property is lacking – because of either the possibility of arrest, ruin, or execution at the command of the ruling prince or the possibility of ruinous taxation – should experience relative stagnation. By contrast, economies in which property is secure – either because of strong constitutional restrictions on the prince or because the ruling elite is made up of merchants rather than princes – should prosper and grow.

Much of the work investigating the relationship between despotism and economic growth focuses on modern economies. The quantity of data available for modern economies is much greater than for earlier economies.

However, there are some limitations from focusing on only modern economies. Long time series are often impossible to compare, because most data is only available for maybe a century. The development trajectories of different countries, both economically and politically, are not independent from each other, so there are fewer independent data points than it might initially seem.

Modern economies might also have different development patterns which cannot be easily replicated elsewhere. Having an abundance of certain natural resources, like oil, can cause a modern economy to grow regardless of its institutions. This often isn’t a useful observation: `Have large hydrocarbon reserves’ is not actionable advice. The development strategies useful for catching up to the technological frontier might be different from the development strategies useful for societies at the technological frontier.

Looking at earlier economies can allow us to avoid some of these problems. The time series can be much longer. The economic and political developments of different countries are less likely to be similar to each other over the entire time frame. Pre-industrial economies were all centered around food production, so there is less opportunity to build an economy based on resource extraction. The technological differences between countries (at least within Europe) were smaller, so catch-up growth is less relevant. Pre-industrial economies provide a set of examples with different limitations than modern economies.

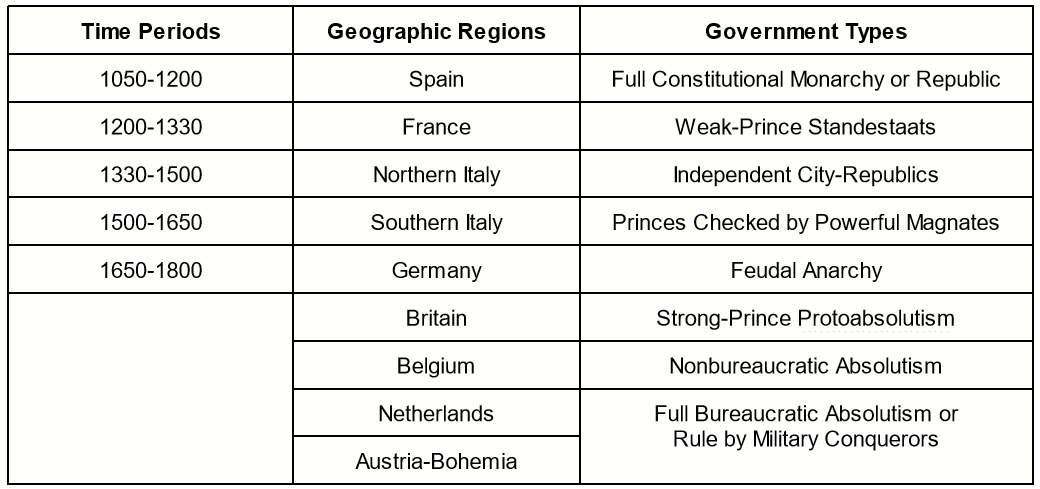

De Long & Shleifer compare different regions of Europe between 1050 and 1800. The growth of cities with a population of at least 30,000 acts as a proxy for economic growth. They divide the time frame into 6 periods, they divide central and western Europe into 9 regions, and they categorize governments into 8 types. All of these categories are listed in Table 1.

The main challenge with focusing on pre-industrial economies is that high quality data is much less available. Urban population is an imperfect proxy for economic development. There are several datasets that estimate the population of European cities over this time period, and they do not always agree with each other.1 There is also some arbitrariness in deciding which system of government was dominant in a region for more than a century. However, the effect size is large enough to be robust to these uncertainties.

This paper was written in 1993 and has over 1,000 citations. I have not looked at how more recent literature has responded to or developed since it was published. It seems to be a classic in its subfield.

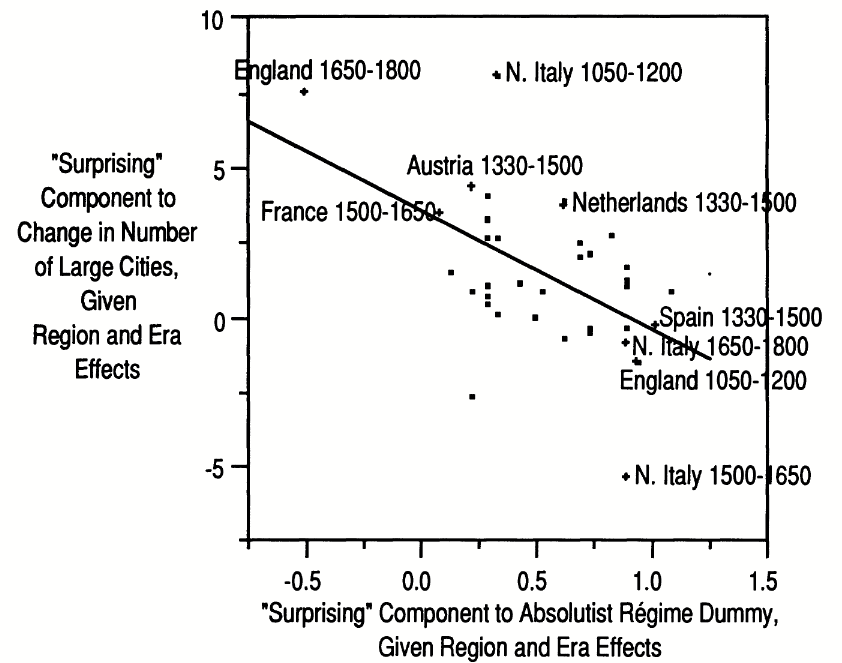

There is a strong correlation between how free a society is and its urban growth (Figure 1).

We find that, on average, for each century that such a region is free of government by an absolute prince, its total population living in cities of 30,000 or more inhabitants grew by 120,000, relative to a century of absolutist rule. This difference is larger than the average growth rate of urban populations in European regions between 1000 and 1800. In a purely statistical sense, therefore, the association between absolutism and slow city growth can more than account for why some western European regions had relatively low rates of urbanization in 1800, while others had flourishing cities and abundant commerce.

Controlling for the region, the time period,2 and whether the city is an imperial capital makes the association even stronger.

Several of the particular examples make it seem likely that this is causal, rather than merely a correlation.

In 1050, southern and northern Italy were similarly urbanized. Over the course of the next century, their political systems diverged. Southern Italy was consolidated under an unusually centralized Norman kingdom. The cities of northern Italy became increasingly independent from the Holy Roman Empire through the Investiture Controversy and Lombard League.3 The cities of northern Italy outpaced the growth of the cities of southern Italy over the next few centuries. Around 1500, the kingdoms of France and Spain reduced the independence of most of the Italian city-republics in the Italian Wars, and the urbanization of northern Italy slowed.

Prior to about 1500, the Low Countries were ruled by the Duke of Burgundy, a weak feudal government with checks on its power. These regions were then transferred to the Habsburgs, an increasingly bureaucratic absolute monarchy. The northern part of the Low Countries rebelled and formed the Dutch Republic. In 1500, the urbanization of the southern (Belgium) and northern (Netherlands) parts of the Low Countries were similar. They diverged dramatically afterwards. Urbanization in the Netherlands increased and they became a global economic power, while Belgium stagnated.

For most of the time between 1050 and 1800, England was an unusually centralized and bureaucratic kingdom. Around 1650, the English Civil War and Glorious Revolution established the supremacy of Parliament on the most important issues. England had been economically underdeveloped prior to 1650, but afterwards saw rapid economic growth culminating in the Industrial Revolution.

While the existence of the correlation is not surprising, it is surprising how clear the effect is. Modern economies do not have this strong of a correlation between freedom and economic growth. With longer time frames and with fewer opportunities for technological catch-up or economies based on resource extraction, the long-term structural differences are more apparent. Medieval and early modern free societies had more economic development than their less free counterparts.

From the perspective of the people alive at the time, or of the long-term growth of the economy, princely success is economic failure. For the people of southern Italy, the creation of the d’Hauteville regno was no blessing; for the people of Belgium, their incorporation into the Habsburg Empire was no benefit; for the people of Iberia, the marriage of Ferdinand and Isabella was no cause for rejoicing. The rise of an absolutist government and the establishment of princely authority are, from a perspective that values economic growth, events to be mourned and not celebrated.

The largest errors seem to be about a factor of 3, for a few of the largest Muslim cities in Europe in 1050.

Some regions might systematically have faster city growth, independent of the institutions. For example, Habsburg Spain had access to tremendous wealth from the New World, while Habsburg Austria did not. Some time periods also had systematically faster city growth. For example, 1330-1500 had the Black Death, while 1500-1650 had an influx of wealth from the New World.

That there is a lot of history here that I am barely mentioning. The other specific examples’ histories are similarly abbreviated.

Really interesting breakdown of “Princes and Merchants” — the point about institutional incentives shaping innovation outcomes resonates a lot. It reminds me of how decentralized and flexible tools can empower individuals to organize and capture insights better, instead of relying on rigid top-down systems. I recently explored something similar while using NOTCAM APP

, which integrates note-taking with real-time camera input — a small example of how better individual tools can foster efficiency and learning autonomy.

https://notecam.app/